Most of the time, your parent's version of their own past is also bakaiti. It's their memory of their suffering, compressed into a morally instructive narrative, with all the ambivalence and weakness and complaining they actually did at the time carefully edited out. They're comparing your honest present to their mythologized past. You can't win.

But these bakait institutions are incredibly stable. They’re almost impossible to kill because they’re not accountable to reality. A car company that makes bad cars goes bankrupt. A bakait institution that produces useless reports just produces more reports explaining why the previous reports haven’t been implemented yet. They’re sustained by the need for the appearance of action. Politicians need to point to something.

To say these things, I have to risk describing something that might only be true for me, which means I can be unrelatable, or worse, boring. Even worse, I might realize I'm responsible for my own misery. I will have to forfeit the safety of narratives and treat my own experience as the only authority, and my life exactly as it is, with no villain and no victim.

If you look at your life, the first thing you notice is how little of it is made of trending issues. Everything that actually happens to you happens at the scale of the moment. Narratives are a retroactive pattern you draw across them.

By this, I don't mean to say that narratives and frameworks aren’t real or don't have any merit to them at all; I mean that their reality is derivative. They exist as stable regularities in the way particular bodies get affected. Lose touch with the particulars and your systems become ghosts unmoored from reality. The point is not to abandon structure altogether, but to earn it, to let concepts arise from lived reality. Kierkegaard said purity of heart is to will one thing. You could say purity of perception is to see one thing, fully, before generalizing. But we generalize first, then go hunting for examples that fit.

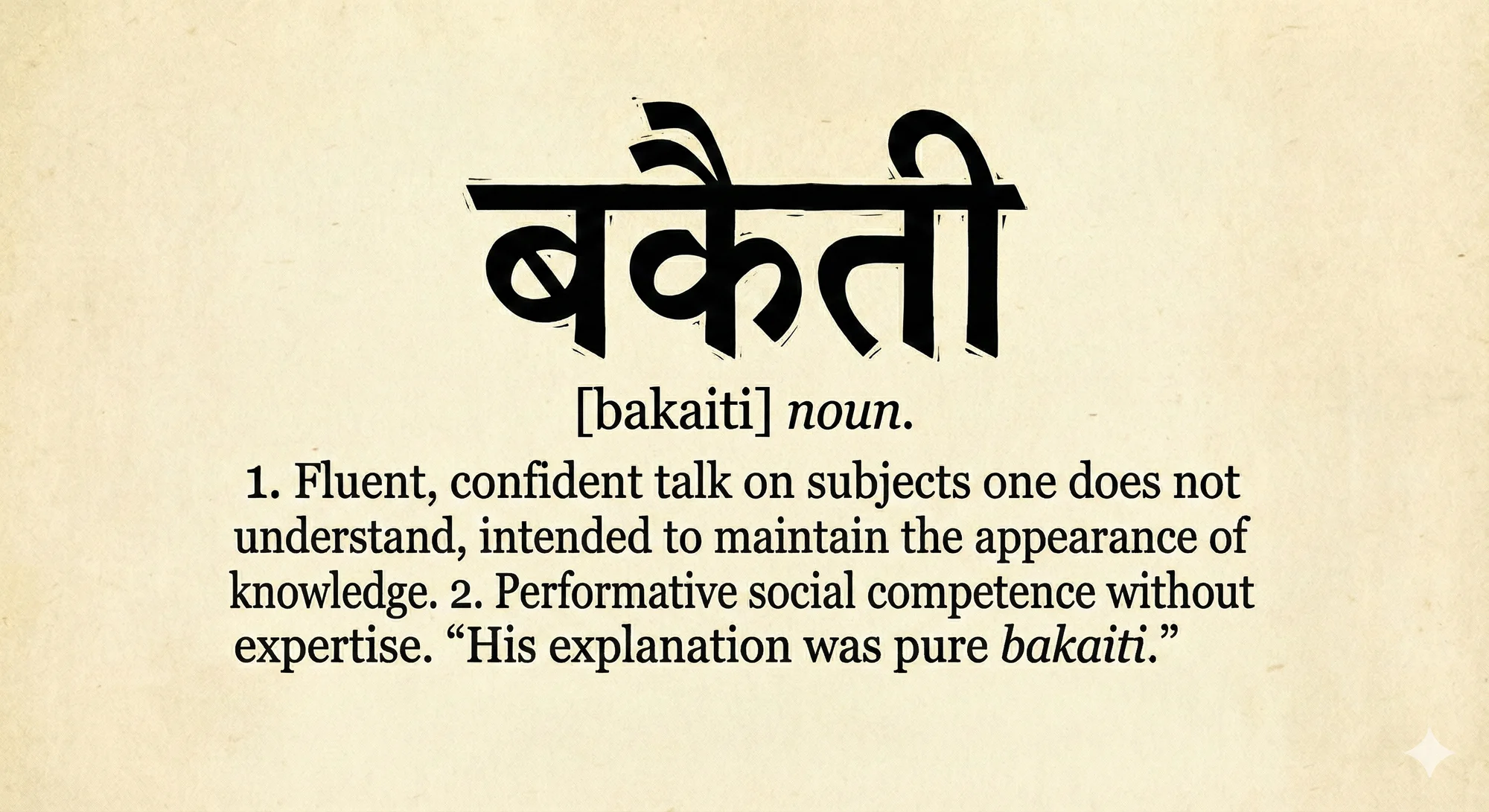

On Bakaiti

There is a familiar Indian habit of speaking confidently about matters one does not in any meaningful sense understand. This habit is often dismissed with the word “bakaiti.” The term is informal, but the phenomenon it names is remarkably stable. A person engages in bakaiti when he produces talk whose primary function is not to describe his experience or justify his beliefs, but to sustain the appearance of knowing. This includes people confidently pontificating about geopolitics, economic policy, or the latest tech trends based purely on what they've consumed from the media, without any firsthand involvement, expertise, or ground-level understanding. Just regurgitating talking points and opinions they've picked up. The talk is fluent, general, and insulated from any demand for precision.

Harry Frankfurt's bullshit is about indifference to truth: the bullshitter doesn't care if what they're saying is true or false, only that it serves their purpose. But bakaiti is performative social competence.

In Indian contexts especially, being able to hold forth on politics, cricket, the economy, international affairs, etc. is how you signal you're educated, aware, plugged in. It's almost a social duty in certain settings. You're expected to have takes. And it's often genuinely well-intentioned! Unlike bullshit, which Frankfurt sees as more corrosive than lying, bakaiti does not aim to mislead about facts. It aims to obscure the speaker’s relation to those facts. The bakait often believes he's engaging seriously with important topics. We all know that whatsapp-forward intellectual whose takes arrive pre-packaged, where complex and nuanced situations get reduced to shareable messages nauseatingly swamped with emojis. This person confidently explains situations they heard about 20 minutes ago as if they've been tracking them for years. He does not care whether his views on science, politics, economics, technology, or human nature are true or false. He cares chiefly that he be seen as the kind of person who has views on these subjects and what side he is affiliated to. His speech is therefore untethered not only from evidence but also from his own lived experience and operates at a scale safely above the level at which he might be held accountable.

Bakaiti as social practice is mostly harmless, even useful. It's chichas sitting around a carrom board discussing China's foreign policy. They're killing time. Pleasantly. Socially. The content of the conversation is completely irrelevant. They could be talking about anything. The point is the sitting together and having a good time with friends. Nobody finishes that conversation and then goes home and does something about China's foreign policy. And that's fine! That's what hanging out is.

Bakaiti is fun at a thela and works beautifully as social lube. But it is disastrous as self-knowledge.

You lose the ability to tell the difference between what you think and what you've heard. Your positions on everything become an aggregation of takes you've absorbed. You can speak fluently on any topic but can't actually trace back to why you believe what you believe.

Your self-understanding becomes third-person. You start explaining yourself using the same abstract frameworks you use for everything else. You say, “I'm an introvert,” “I have ADHD,” “I'm neurodivergent,” “I'm dealing with burnout”, “I have post-covid, ” but you've lost touch with the actual texture of what's happening. And once this gap exists, you don’t ask naive questions or linger with your own confusion. You learn to perform certainty at the level of discourse while feeling helpless in your own life. This helplessness then gets laundered back into more big talk: “It’s all broken,” “It’s all rigged,” etc. The direction of explanation is reversed. Instead of constructing explanations from the grain of lived hours, you measure lived hours to fit supplied explanations.

Cognitively, big abstractions function as schemas that compress reality. They’re useful until they become so dominant that they filter out anything that doesn’t fit. But phenomenologically, this is a corruption of experience. You no longer feel first and think after; you think first in narratives and force feelings to comply, and worse, experience even more conflict and contradiction when they don't comply. “Capitalism is oppressive” might be true in certain contexts, but if it becomes the only lens, you will start interpreting every traffic jam, every awkward date, every bout of insomnia as yet more proof of the system, instead of as events with their own distinct textures and causes. Different root causes get mapped to the same label. Exhaustion, boredom, lack of interest/intent, lack of validation, etc. all get dumped into the bucket of “burnout.”

Once in the bucket, they become harder to discriminate and therefore harder to address.

The result is a peculiar modern stupidity: you turn into a person who can describe catastrophe in eloquent big talk but cannot fix their own life and relationships. Because you can’t fix what you refuse to see! So, you find incredible difficulty in changing any bad habit or behaviour, because now, your beliefs aren't rooted in anything you've directly experienced, so evidence from your own life bounces off. You'll maintain a position even when your own experience contradicts it, because the position exists in a different ontological space of ideas and images rather than your own concrete experience.

And because you can't solve your problems anymore, you experience a collapse in perceived agency. You feel “anxious,” “lonely”, “yearn for another life you're not living yet” but those words float unanchored. You can’t point to the exact insecurity, desire, or fear that produces the feeling. So you can’t change it, either.

A sign of healthy cognition is you notice something, form a hypothesis, test it against continued experience, adjust. But in bakaiti-mode thinking, you adopt a frame, then force your experience to fit it, or simply stop noticing the parts that don't fit. You're living in a simulation of understanding. If you cannot see why you're tempted to pick up your phone and start doomscrolling, you will accept almost any explanation of “distraction” that tech or therapy offers.

Blunt your perception with such bakait abstractions and you get a population that feels vaguely wronged but reaches for the wrong culprit, every time. You nod, share, quote, then return to days that do not change. You value clean narratives that sound smart over looking at your own life. Yet looking at your own life is what actually lets you adjust behavior. Ignore your own life and you live stupidly, even if you sound smart.

You can see all kinds of such emotionally flattening bakaiti in Indian families.

Our parents seem to operate with a finite set of pre-cached responses to all possible situations: a library of ready-made bakait responses, if you will.

You try to explain your confusion about a relationship. Before you finish, your mother interrupts: “End of the day, sab compromise hi hota hai.” She replaces your experience with a maxim. She doesn’t have to ask a single question. Or you come home after a bad day at work. Maybe you got shafted during promotion season, or a project you worked on for months got shelved, or you realized you're being paid less than your colleague.

You try to tell your father. He says:

“Arrey, office mein toh politics hoti rehti hai. You have to learn to adjust.”

Or maybe it wasn't your father. Maybe it was you yourself citing office politics as the culprit.

In either case, notice that your specific situation was never examined.

A general truth was deployed. “Office politics” is a capsule that can be dropped onto any work complaint. It's unfalsifiable. Every workplace has politics, therefore he can't be wrong. The conversation is now over. Once the maxim has been pronounced, there's nothing more to say. The situation has been “understood”, which means categorized and dismissed.

You feel more alone than before you spoke. You wanted someone to help you see what actually happened. Instead you got an easy cop out.

Some other bakait responses Indian parents dish out (and their kids buy):

“Beta yeh hobby hai, this is not how you'll make a living”

“Stable job hona chahiye”

“Pehle settle ho jao, phir sochna”

“You need to think practically.”

The responses are maximally general; they could apply to anyone, anywhere, in any variant of the situation. Which means they apply to nobody, specifically, including you. And they often deliver this with a tone of settled, smug wisdom. In their mind, they aren't being dismissive. They're giving you the benefit of their experience, distilled into portable truths.

But this “distillation” is pure abstraction: too general to be useful, too authoritative to be questioned.

It's worse than just being ignored. If your father just said “I don't know what to tell you” or “I'm not good at this kind of thing,” you'd at least know where you stand. The relationship could be honest. But the bakaiti simulates understanding while providing none.

Your parent feels like they helped. They gave advice! They shared wisdom! You feel like you were heard, but also like you weren't. Words were exchanged, but the specific thing you were trying to communicate never landed anywhere. Over time, you learn not to bring real problems to them. They can't hold them. They'll just collapse them into maxims that sound like wisdom but provide zero guidance.

Then there's the suffering Olympics, a specific subspecies of bakaiti. It asserts that your experience is only valid relative to other experiences. If someone had it worse, your complaint is nullified. So, complaining about your suffering marks you as weak, spoiled, ungrateful. The proper response to difficulty is stoic silence, like they claim they demonstrated when they used to live in much, much harder times.

The marriage conversation is where family bakaiti reaches its peak form.

You're 28. Your parents want you to get married. You're not sure you're ready, or you haven't met the right person, or you're questioning the institution entirely.

You try to explain this.

What you get back:

“Tum soch-soch ke late ho jaoge. Ek baar shaadi ho jaaye, sab apne aap set ho jaata hai.”

“Thinking too much” is presented as the problem, not the solution. Marriage is described as a self-resolving mechanism, you just have to initiate it. Your hesitation is reframed as overthinking rather than a reasonable response to a major life decision. The entire question of whether you want to get married, what you want in a partner, what kind of life you're trying to build... all of this is preempted by,

“Dekho, perfect koi nahi hota. Adjust karna seekho.”

Nobody is perfect, so you need to have realistic expectations. Fair enough.

But what it actually means is don't interrogate your feelings too closely. Don't ask whether you're compatible. Don't notice if something feels wrong. Just commit and then make yourself fit the situation. It's pre-emptive suppression of your perceptual apparatus.

Outside of the Indian family institution, you also find bakait institutions operating internationally.

A bakait institution is an institution whose performative macro-language has drifted so far from its micro-capacity that speech becomes its primary product.

Except for its humanitarian field work, The United Nations is a Bakait Institution.

The UN doesn’t do anything in the sense that a hospital does something or a factory does something. It convenes. It addresses. It calls for. It produces documents with titles like “Framework for Sustainable Development Goals” that are themselves just more bakaiti. Everyone knows this. It’s not a secret. “The UN is useless” is itself a cliche. It is useless at the level it claims to operate (solving global problems) but extremely functional at the level it actually operates (providing a stage for bakaiti).

The primary output is language. Specifically, language at a very particular level of abstraction: high enough that nobody can be proven wrong, specific enough that it sounds like something is happening.

“We must strengthen multilateral cooperation to address climate resilience in vulnerable populations.”

That sentence took someone three hours in a committee to wordsmith. Every word in that sentence was negotiated. “Strengthen” instead of “create” because some countries already have frameworks. “Resilience” instead of “adaptation” because, actually nobody remembers why, but it tested better. “Vulnerable populations” because you can’t say “poor countries” anymore. And at the end of those three hours, what gets accomplished is a sentence that all parties can sign.

The Bakait institution speaks at a scale it cannot touch. It talks about “global peace efforts,” “sustainable development,” “international community,” “collective will,” “multilateral solidarity.” But if you ask,

Who exactly will stop this genocide?

What will change on the ground by Friday?

Which human will do what different action tomorrow?

There is often no one. A spokesperson declares, “The United Nations calls upon all parties to exercise maximum restraint.”

This sentence is spoken hundreds of times a year, across decades, across wars. It requires no follow-through. It enforces no measurable action. So, it cannot fail, because it never commits. The sentences are engineered to sound morally charged while being operationally void.

A bakait institution talks at the continent level but acts at the cubicle level. It doesn’t produce technology or cure diseases or build roads. It produces conferences, white papers, frameworks, declarations, consensus statements, and working groups that produce reports about what other working groups should prioritize. These are artifacts of language, not artifacts of intervention. And institutions reward what they can archive. If 193 countries must agree, then the only thing that can reliably occur is a sentence, not an action. Responsibility is diluted across so many actors that only speech survives. A simple test for a Bakait Institution: Does the organization routinely say things that no one inside it is personally accountable for? If yes, it’s bakait.

Bakaiti is not the same as incompetence. Incompetent institutions try and fail. Bakait institutions speak and avoid trying.

In India, NITI Aayog is largely a bakait institution among many others. NITI Aayog “provides strategic input” and “fosters cooperative federalism.” What does that mean? Genuinely, what does it do? It publishes reports. It holds consultations. Occasionally someone from NITI Aayog appears on TV to explain government policy, which is weird because they don’t make policy. They provide “inputs.”

A group of such bakaits justify each other’s existence. The UN holds a summit, invites the World Bank, who invites various NGOs, who all cite each other’s reports. It’s a closed loop of mutually-reinforcing bakaiti. When nothing improves, you can always blame “lack of political will” or “insufficient funding” or “implementation challenges.” The framework itself was perfect. Reality just didn’t cooperate.

SpaceX can’t do bakaiti. The rocket either reaches orbit or it explodes. A restaurant can’t do bakaiti. The food is either good or people stop coming. Even the NHAI — for all its bureaucracy and corruption — can’t fully do bakaiti.

The common factor here is skin in the game and rapid, undeniable feedback from reality. Bakait institutions exist in domains where feedback is slow, diffuse, or non-existent. This is why the bakaiti flourishes in international relations, policy think-tanks, certain kinds of NGOs, parts of academia, corporate “strategy” roles, and increasingly, tech companies that have gotten so big they’ve lost the tight feedback loop and gone full corpo.

And now, the internet and social media culture has amplified and engendered diverse kinds of bakaiti, at scale.

Once you can consume way more words than you ever could live, language decouples from experience. There's a collapse of fidelity between lived experience and its public articulation. And this is further aggravated with social feeds that flatten everything into bangers; they surface what’s legible, repeatable, and alliance-friendly. You get praised for generalizing, summarizing, taking a legible position. People care more about sounding like they get it than actually getting it at the level where they could predict or alter anything in their own lives. Reinforcing trending narratives marks you as part of the ingroup. And if what you actually feel cuts against the story your group tells about itself, you're incentivized to turn it into another hot take that again becomes a meme-able narrative. These are essentially the signalling and counter-signalling cycles you see online.

But in all this, what gets ignored is the aspects of your experience that don’t map to clean, marketable aesthetic narratives. They end up getting slowly deprioritized in your own attention.

For instance, today, the entire discourse about smartphone addiction and attention spans is people doing bakaiti about their own experience without actually looking at their own experience.

Scrolling lets you feel like you're doing something while maintaining perfect optionality. Any second that it stops being even mildly interesting, you can scroll past. You're never stuck. You're never confused. You're never waiting for the payoff. So it's not that the phone is preventing you from doing the thing. It's that you're using the phone to avoid noticing that you don't actually want to do the thing right now. You don't have anything you care about enough to do instead. So you scroll. The phone didn't create the boredom or the lack of compelling alternatives. It just makes the boredom slightly more tolerable and supplies easy distraction for people with nothing they genuinely care about.

Also, many today have this romantic notion that goes like “I used to read so much as a kid, but now I can't focus for more than 5 minutes.”

But what you don't see is you were engaging with the most engaging option at their disposal even then. You were watching TV and reading comics instead of studying for exams. Now that wasn't some superior attention muscle you had. You were just enjoying something that was designed to be enjoyable. Now you're an adult with a smartphone and a few other screens hooked up to the internet and someone hands you a book about economics or philosophy or something you're made to believe is good because some senpai on X recommended it but it's boring as fuck and you can't get past page 7. And you blame the phone?

No. The book is boring compared to the social media drip. Or more precisely, you don't actually care about the thing the book is about, you just think you should care about it. And the phone is revealing that you don't care, which is uncomfortable, so you blame the phone. Your “potential” is probably not being blocked by the phone. Your potential is probably roughly what you're already doing. This is it. This is the you that exists when nobody's watching.

The moral panic around AI slop and social media and “smartphones are ruining us” is itself bakaiti.

It's bakaiti that serves a very specific function: letting you externalize the problem.

The bakaiti version gives you villains (tech CEOs), victims (all of us), and a clear narrative (we must reclaim our attention). It sounds smart, is shareable, and requires no self-examination.

But the truth is you're bored, you have no intense interests, your life is mostly fine but kind of empty, and the phone fills the gap. You're just experiencing being a person with an okay life and access to infinite entertainment.

People have moviebrained notions of how they should live their life. Consequently, they feel shame about how they actually spend their time. If you can describe your own pettiness, jealousy, boredom, and lack of interest, you can no longer pretend to yourself. People can infer things about your character. They might see you.

So we all intuitively sense it’s safer to perform a generalized stance than to expose a particular experience. This creates a perverse selection effect where the more public the space, the more it fills with people speaking at the widest, safest level of abstraction. Big abstractions are cheap, visible, and make you look smart to your tribe, while being precise about your actual life costs you something, can't be verified by anyone else, and gets you zero status points. When you hitch your wagon to whatever narrative is trending, you're signaling that you're on the right team, that you're clever, that you have the correct moral stance, all without having to expose anything real about yourself or take responsibility for any specific claim. You gain followers by repeating high-level takes your tribe already believes, not by saying something so specific that it might force them to re-examine their own day. And these narratives then get repeated and reinforced socially, on platforms that incentivize the opposite of perception.

But to describe, without conceptual and egotistical inflation, is to refuse the cheap escape into generality. This is terrifying if you’re used to getting praise for sounding deep; it’s liberating if you’re tired of faking it.

So, bakaiti thrives when you experience a mismatch between your inner fantasy of who you are and the factual evidence of who you are. It's a psychological analgesic and a permission slip to avoid looking at an objective 24x7 CCTV footage of your life.

We choose bakaiti because the alternative is having to see ourselves.

Everyone wants to sound wise about the world, but almost nobody is willing to look closely enough at their own life to say anything true.

If you see this truth, then several uncomfortable things follow.

The first thing that happens when you stop doing bakaiti is you become much more boring in social settings, including social media. Earlier, you used to have things to say about every other issue. Now you just have “I don't know, I haven't really cared enough about it to learn and comment.” This feels like you've gotten dumber. But what's actually happening is you're no longer willing to simulate understanding. You're only willing to speak from the small territory you've actually mapped. That territory is tiny compared to the vast landscape of things you used to confidently pronounce on. But it's yours. You've walked it.

The second thing that happens is you start noticing when other people are doing it. And it's constant. Once you see it, you can't unsee it. The whole social world starts to look like a mutual agreement to never admit we're just repeating things we half-remember reading.

The mundane is where the real difficulty lives, because you can't dress it up. You can't make it sound more impressive than it is, whether we're talking about the ideas or your own sense of yourself. You've got to look at what's right in front of you as the primary evidence. Which is harder than it sounds, because it means giving up a lot of flattering illusions about yourself. We all want to believe we care about truth and nuance and getting things right. But phenomenologically, in the actual felt experience of it, truth tends to show up first as some small, concrete, undeniable thing you're honestly a little afraid to say out loud. Without this noticing, philosophy becomes what it increasingly is on X: an exchange of signals among people who have stopped looking at their own lives. The end state is a civilization that can name its pathologies but cannot feel them in the body, and therefore cannot adjust. Everyone agrees “something is off,” but the contact points where “off” can be sensed and corrected have been dismissed as beneath serious attention in favour of prescriptive frameworks, self-help and scientific studies.

If you've ever observed a child, they will never start with general abstractions. A kid in a store is not estimating its ARR. They’re thinking, this cart is loud and this aisle smells weird. How red the apples are. They're enamored by the mannequins. Their phenomenology is unabstracted and therefore exact. Adults train that out of them. A child starts with the concrete. The big explanations come later, as a kind of overlay that adults insist on.

So, from a child’s vantage, the whole adult world looks like a conspiracy to ignore what’s right in front of our noses. The kid is trying to anchor us in the real while we are dragging them into the abstract. And the irony is that we then praise “childlike wonder” and “play” as adults, as if it’s some exotic trait instead of the default mode of being before the self gets colonized by status-driven abstraction.

The sublime vs. mundane split in our lives rides on the same mistake. We treat the sublime as something “beyond” ordinary life, accessed through art or higher pursuits. But if you’ve ever actually watched your own mind loop for three hours through an embarrasing thing you did, you know there is nothing mundane about the intensity of the ordinary. The so-called mundane is just the sublime we are too numb to attend to.

Most people can’t access this level of attention on demand. They've been conditioned, for years, to skip over raw experience and grab the nearest ready-made frame. The second they feel something, a concept slams down from the top: “anxiety,” “FOMO,” “burnout”, “impostor syndrome”, “my ADHD”, “my autism.”

The concept replaces the feeling. More associated concepts rush in and tell you how to feel about it.

So I'm well aware that telling people to notice more is like telling someone with atrophied leg muscles to run. There’s a skill gap. A sensory gap. A tolerance gap. A courage gap. Looking closely at your own ordinary life is often uncomfortable, even humiliating. You see how much of it is imitation. Second, this attention in itself isn’t inherently virtuous or anything. You can get lost in obsessive self-monitoring, treating every sensation as a crime to be interrogated.

But clear perception of small realities is the only reliable way to check whether your claims are true for you, now. Treat all abstractions as suspicious until you can trace them back to a repeatable, describable pattern in your own life. Treat any claim about yourself that cannot be grounded in such moments as entertainment, not knowledge.

The self then becomes less about what narratives you repeat and more about which small realities you’re willing to see clearly.

You might not like the first honest answer.

But at least it would be yours.

The career path in bakait institutions is literally a corruption arc, where each step is a retreat into increasingly abstract work on even more abstract problems. A few years in, you’ve completely lost contact with what you originally cared about and now operate entirely in the dimension of frameworks, mechanisms, and dialogues.

I pick up my phone whenever I feel bored because it reliably makes me feel less bored. I know this is what I'm doing. I'm not confused about it. I'm not helpless. Never in my life have I been good at sustained focus unless I was genuinely interested in something. Every day, social media just reveals that most of what I'm “supposed” to focus on doesn't actually interest me.

This is terrifying if you’re used to getting praise for sounding deep; it’s liberating if you’re tired of faking it.